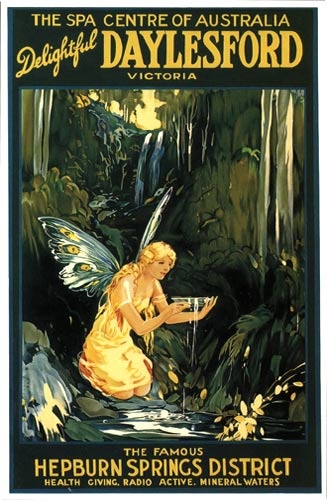

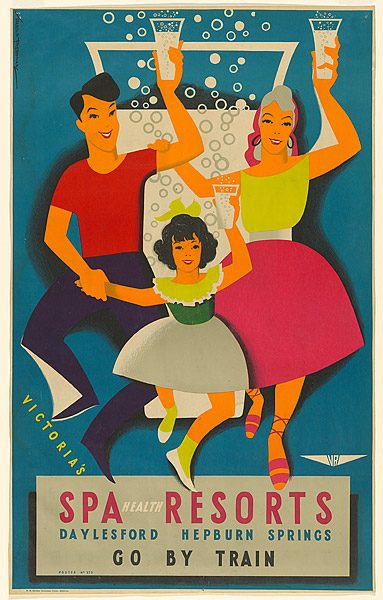

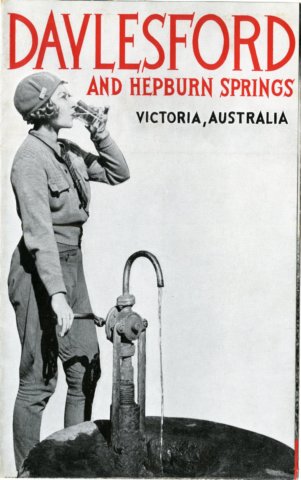

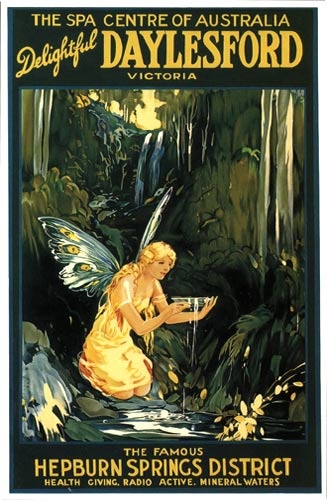

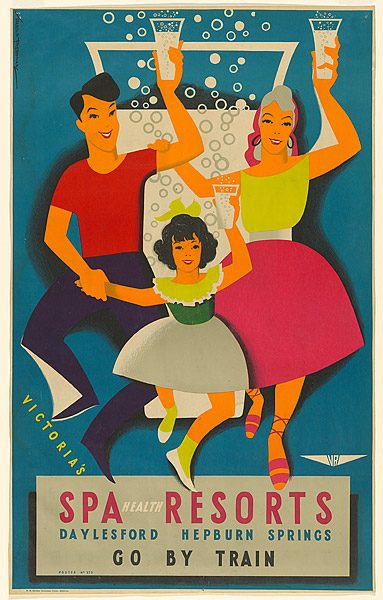

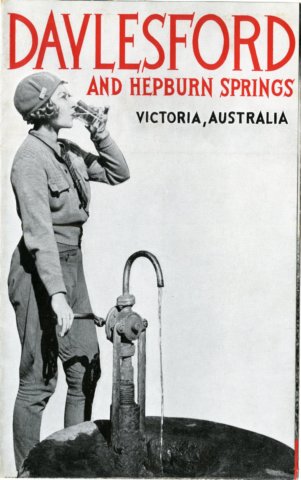

Where I Live: Favourite Daylesford & Hepburn Springs Vintage Tourism Posters

td Whittle

Posted on December 8, 2017

The Dry by Jane Harper

The Dry by Jane Harper

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

*Plot spoilers ahead*

This is such an Australian book, so embedded in local culture that it amazes me it’s popular outside the country. It’s a fine book! But you could forgive someone who, having read The Dry, Wake in Fright, and/or Drylands decided never under any circumstances to visit a rural Australian town. I lived for ten years in Melbourne before moving with my husband to a rural Australian town, and we love it here, but it’s in the central highlands of Victoria and a very beautiful place. Also, we are not currently in drought conditions (though bush fire season approaches and is taken seriously by all of us), and we are not running a farm or dependent on farmers as our customer base.

If you don’t live here and want to understand a bit more about the context of Harper’s story, here’s a timeline of our most recent Victorian drought: 1996-2000: patchy rainfall in the south-east; 2001-2005: El Niño brings on strong drought conditions; 2006-2007: extreme dry and hot conditions in the Murray–Darling basin; 2008-2009: continuing hot and dry conditions; 2009 Black Saturday Bushfires –

worst in Australian history; 2010-2011: La Niña finally breaks the drought. (Source: 2000s Australian Drought.)

During this most recent drought period, I lived in Melbourne and travelled throughout Victoria training and supporting rural support workers, such as psychologists, social workers, financial counselors, addiction counselors (drugs/alcohol/gambling), bush fire counselors, etc. I can tell you now that the distress and pain of the communities facing the death of their livestock, the impoverishment of their families and businesses, and the dying of their towns, is well depicted in this novel. Many of the counselors I was supporting were themselves struggling, financially and emotionally. Farmers were killing themselves at an alarming rate, their bodies sometimes discovered by the rural support workers themselves; disabling depression, alcohol abuse, and domestic violence were on the rise; sheep lay dead in the paddocks (saw this myself, many times); farms that had been passed on from generation to generation had to be sold off to pay debts and feed the family.

Even once the drought had broke, some folks didn’t get a break: mouse plagues arose and devastated their crops. (Wikipedia: In South Australia, only two regions in the Riverland remained in drought. Heavy rains elsewhere led to bumper harvests over much of the state, this in turn led to the largest mouse plague since 1993 across parts of South Australia, West Australia and Victoria. While some farmers tried to replant, in some areas many gave up as millions of mice covered their fields. Farmers often characterised the plague as being worse than the drought.) My husband and I were camping during this time, not yet knowing about the mice and, although mice are not normally scary to me, anything becomes grotesque and scary in plague proportions.

While the drought continued, there was the constant fear of bush fire breaking out which would be apocalyptic for rural towns under such circumstances: dry tinder, hot winds, and the oil in our Eucalyptus forests causing the tree crowns to explode like organic bombs. Finally, this very nightmare occurred, beginning on a day when standing outside felt like some malevolent god was holding a giant blow dryer to your face. It was windy and dry and well over 40C. We called our neighbour and insisted she come to our home and sit in front of the air conditioner. She was elderly and planning to ride out the heat at home but this was no ordinary heat. We drank cold drinks and tried to hold a conversation but, ultimately, our talk died out as we realised that King Lake was burning in the hills. We watched this community and other fires smoking from our terrace the rest of the evening, the smoke reaching our home in the suburbs of Melbourne.

I don’t read many crime novels, but I have a penchant for Louise Penny. I like that she focuses not on the crime so much as the people surrounding it, so that we get inside their heads and hearts and see the world as they see it. I would not say that Jane Harper does this to quite the degree that Penny does. This novel is less complex than the majority of Penny’s Gamache series. In fact, it can be read easily in one or two sittings which I’ve never done with a Penny novel. But I would say that Harper’s strength with building the story around people rather than forensics is like Penny’s. I do not enjoy forensic pathology series. Firstly, they are just gruesome; secondly, they bore me. That is a bad combination. The Dry does have its gristly bits, to be sure; it is dealing with a horrific murder as well as depicting a town whose citizens’ nerves are shredded to pulp. It is raw and gritty and very physical.

Harper does an exceptional job of depicting the physical wear and tear of a hot, dry, hard-scrabble town. I could feel the heat, the despair at looking into an empty river bed, the horrible gasping terror of trying to talk a desperate sociopath out of lighting the bush on fire. The mystery itself is pretty good, as these things go. I was not surprised by the revelations as far as who did what, but nevertheless, the narrative was very well executed. Ruinous gambling addiction is sadly common here, so unsurprising but well chosen as a motivation for murder; timely and relevant in Victoria.[Ruinous gambling addiction is sadly common here, so unsurprising but well chosen as a motivation for murder;

timely and relevant in Victoria. (hide spoiler)]

My only nagging complaint, based on my own experiences in rural Victoria, even during the very worst of the drought and after the 2009 bush fire tragedy, is that Harper did not show much of the kindness and care of these communities. For, despite all these challenges, it is there. I found it again and again. Reading The Dry could make you think that these communities fracture entirely under pressure, so that there is precious little decency or humanity left, and what is there has to be brought in from the outside (Melbourne in the case of Falk; Adelaide for the town’s police chief and his family). On the contrary, there is a strong and tenacious spirit at the heart of many of these towns and these people, and always a core of them who pull together at the worst of times and help each other and the community.

The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy by Mervyn Peake

The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy by Mervyn Peake

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Come, oh, come, my own! my Only!

Through the Gormenghast of Groan.

Lingering has become so lonely

As I linger all alone! (p.99)

Ah, Gormenghast! I (td) have only got through Titus Groan, so far, which is the first book of the trilogy. Here is the blurb for that part of the trilogy, for anyone not familiar with it: ‘Titus Groan starts with the birth and ends with the first birthday celebrations of the heir to the grand, tradition-bound castle of Gormenghast. A grand miasma of doom and foreboding weaves over the sterile rituals of the castle. Villainous Steerpike seeks to exploit the gaps between the formal rituals and the emotional needs of the ruling family for his own profit.’

Initially, I was not enjoying the book. I am not sure if this was due to listening to an audio version, which sometimes works for me and sometimes not, or something else, but mostly, I believe that it was the loathing and malice of the characters towards one another that put me off. Early on in the story, there seemed not to be a single ray of mercy, kindness, love, or hope breaking through the grim darkness. I set it aside thinking I might try again later when not in midwinter.

In the meantime, I ordered this grand illustrated hardcover. After receiving it and noticing its beauty, I could not wait to resume the story. Alas, Keda entered the picture not long after the point where I’d left off! Keda is selected by Nanny to be the nursemaid of Baby Titus, so I could stop worrying that he would be dropped on the stone floor of the castle again, only to have his parents and most of the other adults in the room stare with indifference at his crying. (Disclosure: I worked for a long time with abused and traumatised children so I have no sense of humour when it comes to hurting them, whether they are real or imagined.) From this point on, I was able to enter into the spirit of the novel.

Once you get lost as a watcher and wanderer in the vast and dripping halls of Gormenghast, there really is nothing like it. Perhaps if Dickens had grown up in a haunted castle set in an imaginary land, and co-authored his books with Lewis Carroll, they might have given birth to something similar. There are similarities, to be sure, in Dickens’ genius for soap-opera, Carroll’s brilliance for turning everything topsy-turvy, and Peake’s visionary masterpiece.

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat: ‘we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.’

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

As in Wonderland, so in Gormenghast. If you find yourself in the company of the Groans, you are no doubt at least a bit mad. Nevertheless, after resuming the book, I began to feel connected to several of the characters and concerned for their well-being: Fuchsia, Keda, Titus, and Nanny, especially. But also, I found that the funny bits are really hilarious. I cannot get enough of Cora and Clarice Groan. A scene that made me laugh aloud is when the twins are dressed up for Titus’ birthday breakfast and using one another as a mirror:

There is another silence. Their voices have been so flat and expressionless that when they cease talking the silence seems no new thing in the room, but rather a continuation of flatness in another colour.

‘Turn your head now, Cora. When I’m looked at at the Breakfast I want to know how they see me from the side and what exactly they are looking at; so turn your head for me and I will for you afterwards.’

Cora twists her white neck to the left.

‘More,’ says Clarice.

‘More what?’

‘I can still see your other eye.’

Cora twists her head a fraction more, dislodging some of her powder from her neck.

‘That’s right, Cora. Stay like that. Just like that. Oh, Cora!’ (the voice is still as flat), ‘I am perfect.’

She claps her hands mirthlessly, and even her palms meet with a dead sound. (p.276)

Dr. Prunesquallor, it must be said, is also hilarious, and I am endlessly fascinated by Lady Gertrude, with her cats and birds. Since I have a cat and bird obsession myself, I think she touches some dark part of me that lives in a tower in a semi-feral state, sporting outrageous piles of hair and billowing garments covered in candle wax.

I keep reflecting on the soliloquies and silent reflections of Lord Groan, and I believe that these remind me most of Shakespeare’s tragic kings, especially Lear. This book is a uniquely strange brew of hilarity and sorrow. There is a particularly poetic speech by Lord Groan, who utters it near his sleeping daughter’s door whilst in a somnambulist’s dream himself, that is immediately followed by a long scene of horrific violence between the grotesque cook, Swelter, and Lord Groan’s valet, the angular and spiky Flay. Horrific, yes, but I could also imagine the Monty Python troupe, in its halcyon days, carrying off this sprawling fight to the death with unparalleled gore and glee. So, if I have already said that this book is something like the love child of Dickens and Carroll, I would have to toss in Shakespeare and Monty Python, for good measure, and conclude too that some of the poetry had been inspired by Poe! Really, though, Peake’s writing, taken as a whole, can only be likened to itself. Utterly enchanting, outrageously funny, and brimming with pathos.

To follow, for your reading pleasure and mine, is Lord Groan’s gorgeous soliloquy that I’ve mentioned above, which he utters in his sleep while Flay and Swelter stalk each other and try not to wake him. Lord Groan, having lost his great library (his sole passion and reason for living) in a fire, is saying these words outside the bedroom door of his daughter, Fuchsia. The loss of his library has pushed him from melancholy to madness so that he believes himself to be not a Lord, but one of the bloodthirsty Gormenghast owls. He is saying goodbye and taking himself off to the tower where the owls are known to gather, to offer himself in sacrifice. Perhaps this should read as a parody of Shakespeare but it doesn’t because it is genuinely sorrowful and too lovely by half to be a parody. When one reads it, in context, it is not at all funny but only tragic:

As Flay reached the last step he saw that the Earl had stopped and that inevitably the great volume of snail-flesh had come to a halt behind him.

It was so gentle that it seemed as though a voice were evolving from the half-light ― a voice of unutterable mournfulness. The lamp in the shadowy hand was failing for lack of oil. The eyes stared through Mr. Flay and through the dark wall beyond and on and on through a world of endless rain.

‘Goodbye,’ said the voice. ‘It is all one. Why break the heart that never beat from love? We do not know, sweet girl; the arras hangs: it is so far; so far away, dark daughter. Ah no ― not that long shelf ― not that long shelf: it is his life’s work that the fires are eating. All’s one. Good-bye . . . good-bye.’

The Earl Climbed a further step upwards. His eyes had become more circular.

‘But they will take me in. Their home is cold; but they will take me in. And it may be their tower is lined with love ― each flint a cold blue stanza of delight, each feather, terrible; quills, ink and flax, each talon, glory!’ His accents were infinitely melancholy as he whispered: ‘Blood, blood, and blood and blood for you, the muffled, all, all for you and I am on my way, with broken branches. She was not mine. Her hair as red as ferns. She was not mine. Mice, mice; the towers crumble ― flames are swarmers. There is no swarmer like the nimble flame; and all is over. Good-bye . . . Good-bye. It is all one, for ever, ice and fever. Oh, weariest lover ― it will not come again. Be quiet now. Hush, then, and do your will. The moon is always; and you will find them at the mouths of warrens. Great wings shall come, great silent, silent wings . . . Good-bye. All’s one. All’s one. All’s one.'(pps. 307-308.)

I owe it to the excellent reviews by friends on Goodreads that, firstly, I heard about Mervyn Peake and Gormenghast and, secondly, that I stuck with it long enough for its magical genius to reveal itself to me. A fantastic literary masterpiece!

Note: This review will be ongoing, updated from time to time as I read my way through the trilogy.

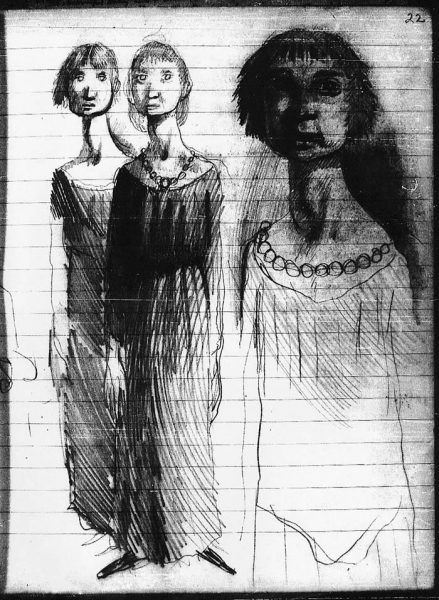

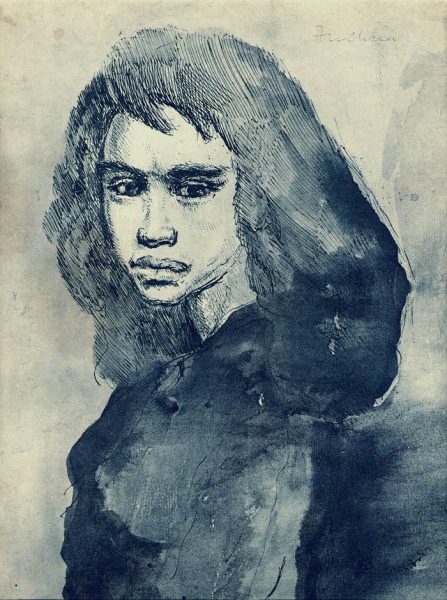

Lady Gertrude Groan, by Mervyn Peake

Ladies Cora and Clarice Groan, by Mervyn Peake

Lady Fuchsia Groan, by Mervyn Peake

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

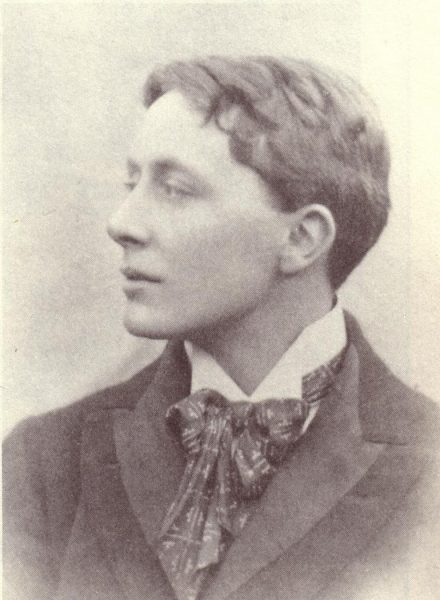

English poet and Dandy, John Gray. As a writer, Gray is best-known for Silverpoints, The Long Road, and Park: A Fantastic Story. Though celebrated in his day, today he is perhaps best known for being the rumored inspiration for Oscar Wilde’s fictional character and literature’s most famous Decadent and Dandy, Dorian Gray.

***Warning: Plot rotters ahead!***

When they entered, they found hanging upon the wall a splendid portrait of their master as they had last seen him, in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage. It was not till they had examined the rings that they recognized who it was.

Friends, whatever you do, think twice before deleting that selfie! Unless, of course, you are certain it does not contain your soul. Personally, I wouldn’t risk it.

Dorian Gray surprised me! I had managed to get this far in life with only catching vague, humorous references to paintings rotting in attics, so I had no idea how rich and complex and devastating this novel is. Up until now, I was familiar only with Wilde’s plays and poems. I read this classic as if it were a thriller. I couldn’t put it down and felt my jaw clenching as I turned the pages. Having said that, my favourite paragraph was a simple, descriptive one:

There was a silence. The evening darkened in the room. Noiselessly, and with silver feet, the shadows crept in from the garden. The colours faded wearily out of things.

Gorgeous writing, as is the rest of the book. In fact, I think this short novel, like its ill-fated painting, is aesthetic perfection.

I have to say, Lord Henry drove me spare. I suppose he was meant to, being the Devil incarnate, but I became impatient with his constant barrage of upside-down aphorisms. What a cold cold cold man:

No, she will never come to life. She has played her last part. But you must think of that lonely death in the tawdry dressing room simply as a strange lurid fragment from some Jocobean tragedy . . . The girl never really lived, and so she has never really died. To you at least she was always a dream, a phantom that flitted through Shakespeare’s plays and left them lovelier for its presence, a reed through which Shakespear’s music sounded richer and more full of joy. The moment she touched actual life, she marred it, and it marred her, and so she passed away. Mourn for Ophelia, if you like. Put ashes on your head because Cordelia was strangled. Cry out against Heaven because the daughter of Brabantio died. But don’t waste your tears over Sibyl Vane. She was less real than they are.

Honestly, I could not bear to sit through an hour with Lord Henry, let alone an entire evening. I found him a tedious bore, forever showing off, in his world-weary way, his grasp of irony via verbal acrobatics. No one stopped to notice that at least two-thirds of what he said was utter bollocks. All readers, I would guess, love repartee between clever characters but, in the case of Henry, birdying his friends’ sentences back at them in an endless badminton of parody and paradox seemed to be his sole mode of communication. Dorian, though, is a tragic figure, like a Greek hero, so one could feel for him even in his worst moments because it was clear from the beginning that he was doomed.

I did not realise how deeply philosophical Dorian Gray is, nor how unsubtly homoerotic (for its era) and overtly misogynistic (for any era). Despite Dorian’s claiming repeatedly to fall in love with women, he is obviously indifferent to them as human beings and seems much more interested in spending his time with attractive young men. Lord Henry is much the same, only the worse misogynist. He enjoys women who amuse him but hasn’t much good to say about any of the sex.

That awful memory of women! What a fearful thing it is! And what an utter intellectual stagnation it reveals! One should absorb the colour of life, but one should never remember its details. Details are always vulgar.

In fact, our artist who creates the famous painting, Basil Hallward (whom I keep wanting to call Hardwood!) is similar to Henry and Dorian in his commitment to aestheticism and his sensuality, but he is a far kinder man who has scruples.

I really cannot recommend this book highly enough for the quality of its writing, its moral argument (which is compelling but ambiguous), and its beauty. Now, I must read Against Nature, or I will feel forever that I have missed something important about Dorian Gray. Hopefully, it won’t poison me or make me any more decadent than I already am!

A feeling of pain crept over him as he thought of the desecration that was in store for the fair face on the canvas. Once, in boyish mockery of Narcissus, he had kissed, or feigned to kiss, those painted lips that now smiled so cruelly at him. Morning after morning, he had sat before the portrait wondering at its beauty, almost enamoured of it as it seemed to him at times. Was it to alter now with every mood to which he yielded? Was it to become a monstrous and loathsome thing, to be hidden away in a locked room, to be shut out from the sunlight that had so often touched to brighter gold the waving wonder of its hair? The pity of it! the pity of it!

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

*** Warning: Plot spoilers running amok ***

Ce n’est pas une histoire d’amour.

(This is not a love story.)

Lately, I have been re-reading some of my favourite great books (Rebecca, Jane Eyre, and Wuthering Heights) and noticing how differently they read to me, as a middle-aged woman, from when I was an adolescent and young adult. One thing that stands out in glaring neon is that the heroes in these Gothic romances are not simply dark bad boys whom love will turn golden. Honestly, younger me did not recognise how very disturbing Maxim, Rochester, and Heathcliff’s behaviours were. It was all in the name of love, after all? Right? Sigh.

This is me, reading Rebecca at twenty-two: Oh my god, this is so romantic! Isn’t Maxim sexy? What’s up with that creepy housekeeper anyway? And that witch Rebecca needs to stay dead! She’s wrecking their romance . . . Alas! True love triumphs in the end! So sad about Manderley though 🙁

And this is me, reading Rebecca at fifty-two, whilst composing a letter to our nameless heroine in my head:

Dear nameless heroine, (Dear god, girl, why don’t you even rate a name?)

In the beginning, I wanted to beg you to please walk away from this man before it’s too late, but then, of course, there’s no story. I realise that your employer, Mrs. Hopper, is a vulgar, nouveau riche monster, but Maxim de Winter, however handsome and rich, is secretive, manipulative, and unyielding. He is a subtler kind of monster, but a monster nonetheless . He will devour you whole. Does it seem not at all odd to you that Maxim is so darkly moody on your dates, or that he has not tried to kiss you properly, even once, let alone seduce you?

Too late now. Nameless heroine, you’ve married him. I understand how his good looks, wealth, and detachment can be seductive. Also, you get to honeymoon in Venice. We are all tempted by such fates, especially when young and alone in the world. Now, you finally have a name and a distinct identity: Mrs. de Winter, wife of Maxim and mistress of Manderley. Well, not distinct actually. All of those belong to him, just as you do.

You are right that the housekeeper at Manderley, Mrs. Danvers, is emotionally unstable and certainly creepy, but she is also grieving Rebecca. Maybe you should try talking to her instead of running away like a scared mousey every time she appears? Why do you listen to the estate manager, Frank Crawley, AKA Maxim’s best friend, but never once ask Mrs. Danvers what her experiences at Manderley have been like? Doesn’t the extremely close friendship between Max and Frank ever make you wonder? I mean, now you are married, you still sleep in separate beds and Max is cold cold cold.

But, we plough on, even though it’s become evident that this is not turning into the dream life you’d anticipated. Eventually, your dear Maxim, his back to the wall, admits to you that he murdered his first wife, cleaned up the mess, and then dumped her body into the deep, dark sea. But you are all Stand By Your Man because Love <3 <3 <3 and because, at last, he has said the only words that really matter to you, what you wanted to hear all along: he hated Rebecca, but he loves you. Isn’t that beautiful? Never mind that, up to this point, he has not bothered to say I love you even once. Convenient to do so now though. Surely, his version of things is the Absolute Truth? Right?

Be that as it may, you will live forever in exile, wandering from hotel to hotel across old Europe, playing nursemaid and servant to an aging gentleman who is as remote, fragile, and sexually unavailable as an antique china doll. Just as he warned you early on in the novel: ‘So that’s settled, isn’t it? he said, going on with his toast and marmalade; instead of being companion to Mrs. Van Hopper you become mine, and your duties will be almost exactly the same. I also like new library books, and flowers in the drawing-room, and bezique after dinner. And someone to pour out my tea. The only difference is that I don’t take Taxol, I prefer Eno’s, and you must never let me run out of my particular brand of toothpaste.’

He murdered Rebecca and claims to love you. But he has just as surely murdered you too. It’s a subtler kind of killing but leaves you just as dead.

Rest in peace, nameless heroine.

Love,

a reader

Other letters I keep meaning to write, under the heading: Heroes who should come with warning labels.

Dear Jane Eyre,

Rochester locked his first wife in the attic. I know you know that, but just thought you could do with a reminder. Also, dressing up and pretending to be an old woman fortune teller so that he could interviewing you in disguise? Super creepy.

Love,

a reader who did not marry him

Dear Catherine,

Heathcliff is a psychopath.

Love,

a reader who totally gets how sexy he is but no, just no

A Strangeness in My Mind by Orhan Pamuk

A Strangeness in My Mind by Orhan Pamuk

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

“I can only meditate when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think; my mind works only with my legs.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau

“I will sell boza until the day the world ends.” Mevlut Karatas (p. 584)

This book is long and meandering, its power like that of a fire built slowly from a bit of kindling and a single spark. From the beginning, it is carefully tended and coaxed along in a quiet but steady fashion until Whoosh!, it ignites in full glory.

A Strangeness in My Mind did not particularly grab me, in a dramatic sense, with its opening but it did interest me enough to keep going. It begins with the protagonist, Mevlut, a boza seller, and his fiancee, Rayiha, running away to elope. I liked Melvut and Rayiha, so I kept reading, all the while thinking that, yes, it is good; I am not loving it, but neither do I want to abandon it. We follow Mevlut’s life from the time he is a boy of twelve until he is a man of fifty-five. The narrative structure is mostly linear, though there is a bit of slipping back and forth in time. There are a lot of characters in this book but I did not find them hard to keep track of. However, should you get lost, the author has provided a family tree at the beginning of the book and a character index and chronology at the end.

I felt bogged down in the years when Mevlut was an adolescent living alone with his father on the outskirts of the city, failing at his all-boys school, working as a street vendor, semi-stalking women he was obsessed with, and masturbating nonstop. Then, when Mevlut enters his mandatory military service, the book remains very male-focused, dominated by their interests, their dialogue, and their competitive struggles. Basically, these pages wreak of testosterone and musky sweat. As a woman reader, this bored me, I have to admit. I read a lot of books written by men, but I like the women and girls to be involved or I simply can’t connect. *

Having said that, I did love wandering with Mevlut through Istanbul and hearing about the changes the city was undergoing over the years. And what happened over the course of the narrative is that my sense of intimacy with Mevlut and with Istanbul grew closer, insidiously, so that by the end I was shedding tears and felt a deep sympathy with him. Mevlut is within the city but the city is also within Mevlut. It is also a dynamic symbol of the tumultuous lives of impoverished Turkish families. Their fates and sorrows are intertwined.

So this is how Mevlut came to understand the truth that a part of him had known all along: walking around the city at night made him feel as if he were wandering around in his own head. That was why whenever he spoke to the walls, advertisements, shadows, and strange and mysterious shapes he couldn’t see in the night, he always felt as if he were talking to himself. (p. 579)

I cannot escape my impression that, if one were to put a gender to Istabul, it would be a woman: a grand and beautiful dowager who has been roughly treated but maintains her dignity and grace nevertheless. This is how the women in the book are presented, too. Though not all are roughly treated, they all have difficult lives, made all the more difficult by living in an oppressive patriarchy and struggling at various time with grinding poverty and lack of proper reproductive healthcare. In this way, I came to feel that Mevlut loved three women deeply and passionately during his lifetime: first, his crush, Samiha; then, his wife, Rayiha; and, from the age of twelive, his adopted city, Istanbul.

But just like believing in God, falling in love is such a sacred feeling that it leaves you with no room for any other passions.

By about halfway through A Strangeness… had hooked me. I realised how completely invested I had become in the characters’ well-being. I had not felt terribly attached to Melvut before then and, really, it was the women becoming more of a presence in the book that made it take off for me (Melvut’s wife, Rayiha, their daughters, and Rayiha’s sisters). Over six hundred pages, I fell in love with Melvut, Rayiha, their girls, the girls’ aunties, and the rampaged and rambling sprawl of old Istanbul. These are very ordinary people, with ordinary lives, but the story of these lives is rich and proves the point that no one’s story is boring if you attend closely enough to the telling. Pamuk is masterful in the telling, but it’s a subtle mastery. He does not bash you over the head with bigness. The dramas, while intense and worrying, are not over-played. There are deaths, even one murder, but the details given are only enough to tell us that these things happened. Nothing gratuitous. I appreciate Pamuk’s discretion and feel that his choices of when to zoom in and out of focus are near perfect.

I am reflecting on the aftertaste of A Strangeness in My Mind, thinking that it’s probably a lot like boza: nostalgic, sweet, and just a bit sour, all at the same time.

“No, I’m not joking. Boza is holy,” said Mevlut.

“I’m a Muslim,” said Suleyman. “Only things that obey the rules of my faith can be holy.”

“Just because something isn’t strictly Islamic doesn’t mean it can’t be holy. Old things we’ve inherited from our ancestors can be holy, too,” said Mevlut. “When I’m out at night on the gloomy, empty streets, I sometimes come across a mossy old wall. A wonderful joy rises up inside me. I walk into the cemetery, and even though I can’t read the Arabic script on the gravestones, I still feel as good as I would if I’d prayed.” (p. 271)

Two desires that will linger with me now are to wander aimlessly through the nighttime streets of Istanbul and to try boza for myself. Pamuk is a beautiful writer. I am looking forward to more of his books.

* Note: For this reason, although I enjoy fantasy, I did not enjoy The Lord of the Rings, in which females are icons on pedestals rather than playing an active role, or Moby-Dick or, The Whale, or Das Boot, in which females have no place at all. I did like watching the films of Lord of the Rings though because they were spectacularly made. I was swept away by the awesome visuals.

Margaret the First by Danielle Dutton

Margaret the First by Danielle Dutton

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, is presented here as a vibrant, fascinating, unique, and lovable woman, which I’ve no doubt she was. She was also (perhaps unintentionally) hilarious and egocentric to an astounding degree, but no more so than many men of that or any age. Egocentricity always stands out in a woman of past centuries because it’s so unexpected. One suspects it would not have been tolerated had she not been of noble birth and marriage. Happily, for us, Margaret was protected by the good fortune of both. She is most certainly a shining example of a woman who indefatigably pursued her life’s work and her social, intellectual, and artistic interests, despite the criticism of her peers.

Whilst reading this book, I found myself being constantly grateful to William for standing by Margaret no matter how outrageously (for the time) she behaved. William and Margaret, as presented by Dutton, are a devoted couple who marry for love. They are mutually supportive of one another. William encourages and indulges Margaret’s writing, her autodidactic education, and her whimsical sense of style. Of course, all husbands should do, but I mention this because it was not typical of husbands at the time. William, in this way, was also unique.

Margaret’s fashion choices get a lot of attention in Dutton’s book because they are singularly unforgettable. One evening, Margaret appears at court to meet the new queen in a dress with such a long train that the maid has to stand outside the door holding it, thus Margaret upstages the queen herself. It is a rule that one may not wear a train longer than the Queen’s but Margaret has not remembered this. William takes it in stride and promises to make it all right with the king but, really, the best part of all this is the description of the dress itself: At last they disembark and enter the Banqueting Hall together, William greeting familiar faces, Margaret in diamond earrings and a hat like a fox that froze. . . . in a gown designed to look like the forest floor, like glittering yellow wood moss and starry wood anemone and deep-red Jew’s-ear bloom. It has a train like a river―so long it must be carried by a maid―yet hitches up in front, so she might walk with ease. Gone are the golden shoes with gold shoe-roses, just flat boots laced to her knees. (pps. 136-137) On a related note: I want that outfit―but obviously, the fox hat would have to be fake because I love foxes.

On one occasion, William fails to appreciate Margaret’s choice of dress. She arrives at the theatre wearing a gown that fully exposes her breasts to a crowd attending the performance of a play he’s written. (It also stings that everyone in London assumes that Margaret herself has written the play.) Still, William does not react like a beast, as many men would have done. Here is a description of her costume for that particular evening. (She is always turned out in spectacular fashion!): She has her mask, her gown. The ‘femme forte’ she explained to the seamstress. And so the dress, like an Amazon’s, is all simple drapes and folds. . . . A glass bead in the back of her mouth holds the mask in place. . . . She tries not to gag on the bead. . . . her dress is gold, her breasts bared, her nipples painted red.

The dialogue between William and Margaret, at the end of the play, made me laugh out loud:

. . . but before Margaret can say a thing in all that noise, William has her elbow and is guiding her through the crowd.

“Congratulations!” she tells him once their carriage door is shut.

“No, no,” he says, “congratulations to you.”

The horses lurch ahead, crossing the Fleet in the dark.

“Is something amiss?” she asks, placing the mask in her lap.

The river oozes beneath them, a blacker sort of black.

“What could be wrong?”

The driver turns north onto John.

“Only tell me,” he finally says, looking out into the night, “exactly who wears such a gown to an evening at the theater?”

“The ‘femme forte’,” she explains, “a woman dressed in armor.”

“Do you think you are Cleopatra?” he asks.

Margaret bristles. She fingers the mask. “I had rather appear worse in singularity,” she says, “than better in the mode.”

“Do not quote to me from your books,” he snaps.

The driver flicks his whip. (p.140)

Whilst reading Margaret the First, I was repeatedly reminded of one of my favourite writers, another inspirational woman of history and a legend in her own time, Madame Colette. Though Colette did not involve herself in politics or science, she was certainly a singular sensation and a shining star of the Belle Epoque. Like Margaret, Colette was an intellectual, an autodidact, and an egocentric who challenged the cultural mores of her time; even amongst Parisians during the decadent Belle Epoque, she knew how to cause a stir. She was outrageous and unpredictable, charming and loveable. I thought of Colette’s costume in La Chair (above) when I read about Margaret’s breast-revealing la femme forte gown. Colette was an unrepentant sensualist and a bon vivant of epic proportions who loved to shock and delight a crowd, but it is significant that she came two hundred years after Margaret and, for her time, was no doubt less radical than Mad Madge. Margaret bared both breasts to the public,* without the protection of an acting role and a stage to play upon. She wrote books when women did not write. She thought and spoke at length about politics, philosophy, and science, and made gifts of her own books at a time when women of the nobility were meant to give birth to male heirs, refill tea cups, and then sit quietly sewing in the corner.

This book was not my introduction to Margaret. About a decade ago, I tried to read The Blazing World and Other Writings, drawn in by both the title and what I knew of its author. Alas, I could not get through it. I love Mad Madge as an historical personage of distinction and flair, and I love her ideas. It is so disappointing to me to find them poorly executed and monotonous to read. The book began to feel like a chore to be completed rather than a pleasure to indulge in.

Dutton is a beautiful and subtle writer who does great honour to this inspiring woman. I often think that novels can tell the truth better than biographies, and certainly better than autobiographies. Of course, whether Dutton has captured the essential nature of Margaret and the life she led, we can never know for certain. I like to think she has because it is a beautiful homage she has written, even if it is fiction. Margaret herself lived her life more in her mind than anywhere else, and Dutton certainly captured that about her. You will not find this book a chore at all.

Note: Besides the woodland gown with the faux-fox hat, I now need some stars to paste on my cheeks too.

* Regarding the baring of breasts: It is true that, throughout history, some noble women have been painted or sculpted with one or both breasts bared. Saints, of course, were often depicted in this manner but those were mythic paintings, not portraiture. The baring of breasts was rarer, but not unheard of, in the peerage of England during the Restoration. It is also true that Margaret was not the first female public breast-barer who did it for reasons of personal aesthetics rather than political protest (i.e. Lady Godiva), but I’ve no doubt that she was also making a social point about women being individuals and persons in their own right. Nevertheless, the trendsetter Agnès Sorel beat Margaret by two hundred years: In 1450, Agnès Sorel, mistress to Charles VII of France, is credited with starting a fashion when she wore deep low square décolleté gowns with fully bared breasts in the French court. Other aristocratic women of the time who were painted with breasts exposed included Simonetta Vespucci, whose portrait with exposed breasts was painted by Piero di Cosimo in c.1480. See décolleté

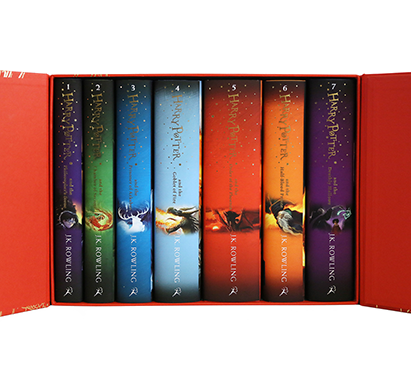

Bloomsbury Publishing: Celebrating Harry Potter’s 20th Anniversary. Boxed set with illustrated covers by Johnny Duddle.

I began reading the Harry Potter series soon after the first book was published, way back in 1997. Initially, this was because I was working as a therapist at a social work agency which specialized in helping children and adolescents. Every child who wandered into my office was talking about Harry, Hermione, Ron, and Hogwarts. They all wanted owls. So, as I always do when working with kids, I studied what they loved so that I could enter into their world with them. Unlike Yugio or the Avengers or Spider Man, though, I found myself as enthralled with J.K. Rowling’s books as any of the children. Also, I will be forever grateful to Rowling for getting a whole lot of kids reading who were uninterested in it prior to the Harry Potter series. (Likewise, whatever we think about the Twilight books, I know for a fact that a lot of semi-literate adolescents improved their reading skills with that series. For that alone, they are worth taking seriously as having made a contribution to our kids’ well-being.)

Here we are two decades later already, celebrating Harry’s magical takeover of the book world. As I no longer have any of the books I read originally, my husband bought me this beautiful boxed set of hardcovers published by Bloomsbury. The cover and box illustrations are wonderful. I like them better than the originals I read, which were the American editions. What I like, too, is that the words and spellings used in the text are British rather than American terms, which is appropriate given that Harry and his friends are all British. So far, I have re-read only the first book, but I am happy to say that it has stood the test of time. Still enchanting!

Bloomsbury Publishing: Celebrating Harry Potter’s 20th Anniversary. Boxed set with illustrated covers by Johnny Duddle.

From the Wreck by Jane Rawson

From the Wreck by Jane Rawson

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

*** Plot spoilers alert ***

I am starting a new bookshelf for Jane Rawson. I had never read her until now, and I just love this book to bits. From the Wreck weaves a tale based in a completely believable “real-world” Port Adelaide of the 1850s, but the net is shot through with luminous (or, rather, bioluminescent) threads of magic. The book keeps us floating in a sense of timeless wonder, drifting back and forth between the hard reality of life on land with the “boot stompers” and the beautiful world that simmers and shimmers beneath the ocean’s waves.

Rawson’s characters are immediately engaging and memorable. I especially appreciate that she avoids the common themes of so much Aussie fiction I have read, where every family is miserable, domestic violence is rife, everyone is marked by trauma, and there is no such thing as a happy or hopeful ending. Rawson treats her characters with compassion and allows them the chance for a good life. Even while they may not always behave admirably, we can understand that they are doing the best they can in very trying circumstances, with their own limited understanding of their situation.

My favourite parts of the book are the passages where the reader is allowed inside the alien/octopus’ mind or inside Henry’s or George’s mind when they are seeing life through her eyes. These scenes are written with a light touch but a deep poetic serenity that is breathtaking:

. . . All of it, life.

The great joyous throb of it.

He plunged into the swarming ocean, felt its wriggling abundance. Slumped and lay soft on the currents of it, drifting. Henry sounded the ancient depths of his Mark ―like this today and yesterday and tomorrow and always. No shadows fell, no teeth snapped and there was a stillness amid the frenzy. Henry felt his place in it ― just to be this boy and never wonder why or who or how to be better, braver, otherwise. Just to be and to love. To notice it fresh every day.

Image source: Liv at Deviant Art

Rawson is also funny, and From the Wreck is compulsively readable. Once I got going, I had difficulty putting it down to do other things (always a reader’s dilemma, but some books make it more of a struggle than others). Here is an example of Rawson’s humour. The alien creature, a giant blue octopus, has morphed herself into the shape of a woman so that she can once again confront her first human companion, George, whom she met and bonded deeply with when he was stranded at sea after the shipwreck. She hopes to set George straight, since he is rollicking around acting like an insane idiot believing that she has somehow cursed him and his boy, Henry. In fact, our shape-shifting cephalopod is not evil and is Henry’s closest companion and most intimate friend. George seeks to sever that bond in a dangerous and potentially fatal way.

So, the alien, who calls herself Bridget when embodied as a woman, is sitting at a bar in a pub, trying to make small talk to get George’s attention. She is unused to being in woman form these days. She is unused to speaking to others. She has never been in a pub and, trying to be like the locals, orders beer for the first time. After spewing the beer everywhere, here’s what she says to the woman sitting next to her:

“It’s a bundle of mysteries, isn’t it, this world? . . . Always something else. Horses. Sandwiches ― have you tried those? Walking on two feet. Leather ― it’s made out of the skin of other living creatures, I found out. Singing, and sometimes everyone knows the song and they all sing too. You can take the fat from a whale and put a flame to it and then you have a light to read. Or sew ― that’s a thing people do. Well. And now beer.”

The beauty of the book, besides the characters, the eulogies of the octopus for her lost home and its people, and the elegant and luminous prose throughout, lies also in its themes: that we humans are easily frightened and fragile creatures who cling desperately to what we know and fear anything strange or different from ourselves; that we might live larger, freer, and much more wondrous and beautiful lives if we opened our hearts and minds to the great unknown, and told our fear to shut up now and then; that we, all of us, are a part of this net of life that spreads out to catch not only our planet, but the universe entire; that we all get lonely and need others, even if human need expresses itself differently from other life forms.

It’s really a gorgeous, enchanting read and I would encourage you to pick it up yourself. The cover is beautiful, too, though I did wish the back had pictured Bridget in octopus form. But that’s just me, being a cephalopod lover. I’ll finish with my favourite quote, whereby George is getting a telling-off by the octopus:

“You didn’t understand anything, George, . . . Why were you so angry? You lived, you fool! You got to have a whole wonderful life on a beautiful world and all you could do was rage against it. I should pull you under these pitiful waves and let you drown in three inches of water. You mean nothing ― nothing. None of anything that happened on that ship meant anything at all. You’re a speck, a tiny speck in time, in space. Nothing. Look.”

And then the voice showed him a story.

On a planet, all ocean, there was a small, happy person living small and happy and quiet in her own small niche, her own small place, her own quiet space. Born, grew, ate, grew, lived, loved, ate. The sun, that star, shining on her one happy face.

Image source:Klaus Wiese, I’m blue, at 500px

The Girl of Ink and Stars by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

The Girl of Ink and Stars by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I have three young nieces who love reading and being read to, so they get quite a lot of books from my husband and me. But I like to read them first and, if they are suitable, buy fresh copies for the children. The nieces enjoy stories about spunky and capable girls with bright minds and big dreams, and this one seemed to tick all the boxes.

So I began this book a few weeks ago but then got distracted with other things I was reading. I picked it up again two days ago and found that I could not reconnect with the story. I started to pitch it into my “DNF” stack. But, no. . . . Something was bothering me about that. I felt I was being unfair. I thought that perhaps I had not been in the right frame of mind to began reading it when I did, as I had just completed book three of Catherynne M. Valente’s The Fairyland Series and some other (adult) books. I decided to begin again and consider The Girl of Ink and Stars in its own right.

I read it straight through in a few hours last night and very much enjoyed it. I think it’s an especially good read for the age group at which it is aimed (middle readers), and I know that I would have adored it back then. Here’s what I found beautiful about it. Firstly, it is gorgeously presented, and I liked everything about this design and presentation. You can see the cover but not the inside, which has maps printed on the inside front and back covers, and cartography bits and pieces lightly printed on each page of text. Secondly, the story is told with simple but elegant language and with compelling characters. Thirdly, the three main characters: Isabella and Lupe, who are thirteen, and Pablo, who’s a bit older, are intense and earnest and take themselves and their challenges very seriously. I like this especially because the book is not funny at all. Not that I don’t like funny books, in their place, but I find it tiresome when books for kids (or adults) deliver lines as if we were reading a script for an American sit-com. Too much sarcasm and snappy one-liners become tedious, annoying, and unfunny very quickly. (This is also a trend in urban fantasy and other genres.) Fourthly, and what I especially appreciated about The Girl of Ink and Stars, the two girls are genuinely left, on their own, to resolve the crisis that threatens to destroy their island home. It is an overwhelming and impossible task, yet they face it nobly and with great character, despite great personal sacrifice.

I think Hargrave uses the island myth to great effect and is consistent and steady with her modern (within the book’s context which has a 19th-century feel) parallels and revelations. She describes things perfectly, as one might expect from a poet, without overdoing the language, giving the reader just enough detail to share her vision. Many times, this vision becomes horrific, and we can feel the terror that Isabella and Lupe and Pablo must feel, but never is it graphically spelled out in grotesque detail. I find this blend of talent with restraint rare these days when so much in books and films is overdone so that absolutely nothing is left to the audience’s imagination.

I would recommend this book to anyone who enjoys reading myths, fairy tales, and folklore, or books about girls who are steadfast and loyal friends saving their world together. (And who doesn’t love that?)

Extra notes for true book geeks: The mapping coordinates of the fictional Isle of Joya are given on the opening page of the book, so of course I went to Find Latitude and Longitude and looked them up! Hargrave has based her tale on La Gomera in the Canary Islands, Spain. This is the very port from which Christopher Columbus set sail on 6th September 1492, intending to sail to the Indies under the patronage of Queen Isabella. Water from La Gomera was taken to “baptise” the new continent. No doubt alluding to these historical facts, in The Girl of Ink and Stars, Isabella’s father, called Da, is a brilliant cartographer who teaches his daughter all he knows of both legends and map-making, and who yearns to see Amrica.

Although it has these real-world overlaps, Hargrave’s Isle of Joya, legend has it, floats! More than simply floating like a scoop of ice cream in a Coke float, though, it travels the globe as its own organic, self-directed, and self-maintained ship. When the story opens, however, the island is held fast to its underwater plates (or by a fire demon – same/same) and the songbirds have long fled. The islanders’ geographical seclusion makes cartography a wild romantic ideal rather than a bonafide profession, especially since the citizens of Gomera are not even allowed to travel across their own lands but must stay put by the coast. Obviously, this presents a challenge for anyone with wanderlust. Some of the other places names mentioned are Amrica, Afrik and India which adds mystique to places that we readers would normally think of as just ordinary parts of our world.