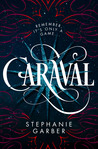

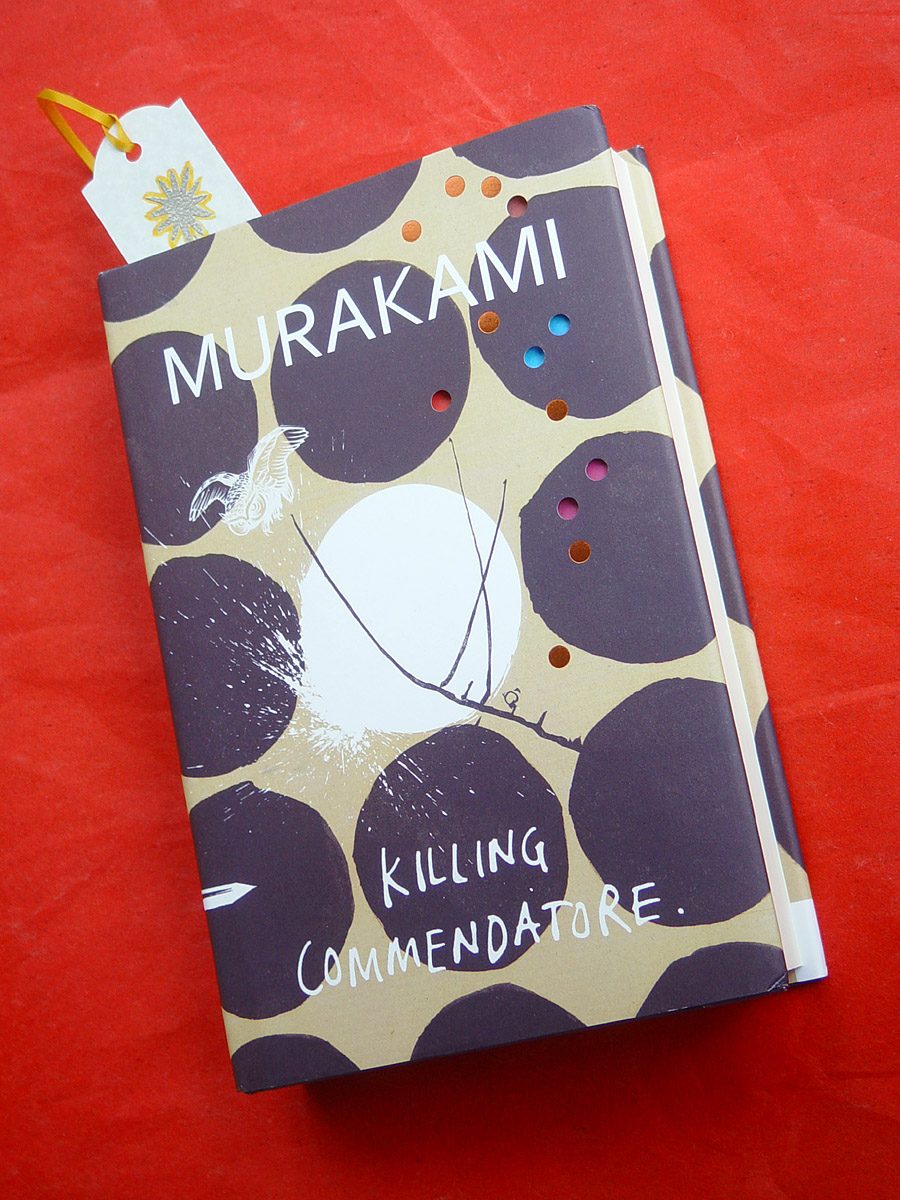

Look what just arrived in the post! Of course, I’ve also ordered the American edition―this one is the British―from an independent bookseller in the U.S. because it comes with a free Murakami book bag (Because one can never have too many book bags, yes? Especially when they have black cats on; or, in the case of my Harper Lee bag, a mockingbird.)

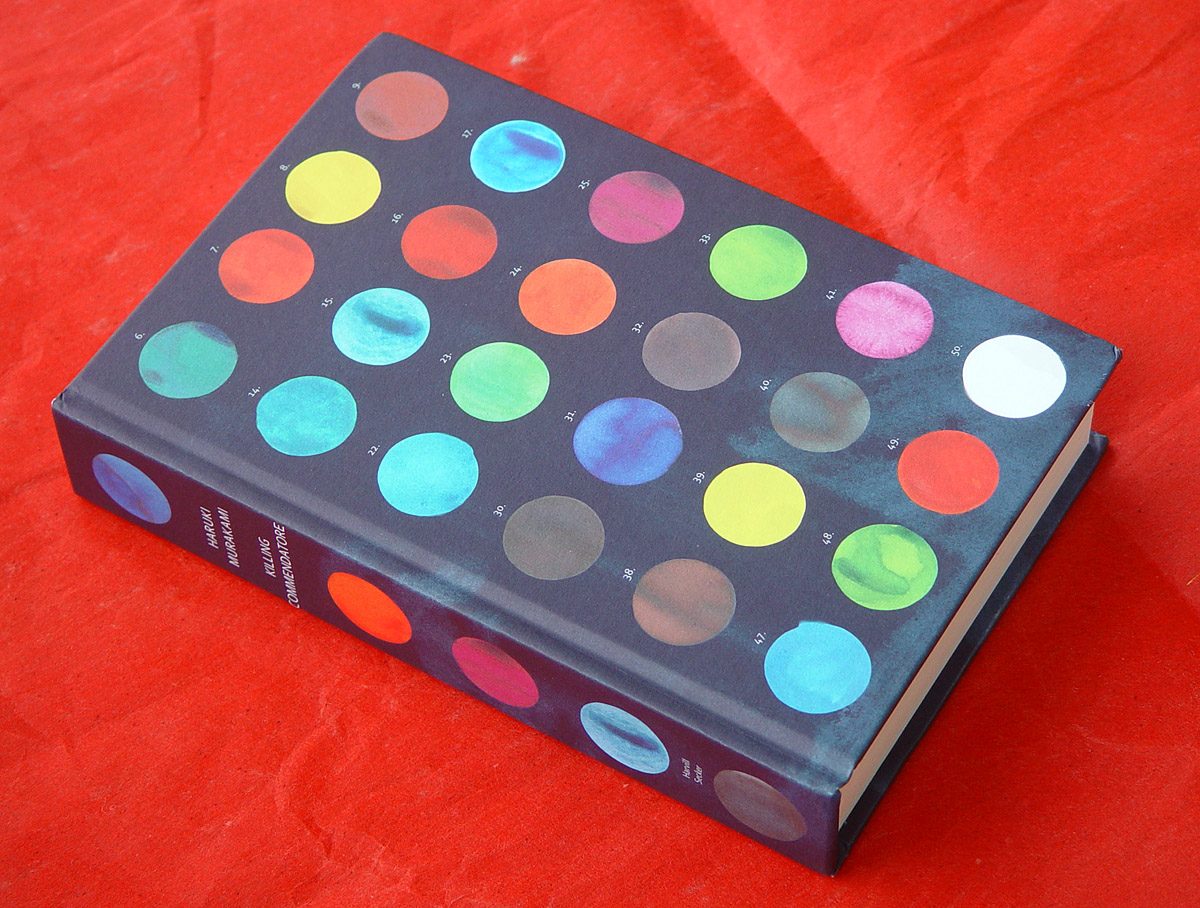

This is the Harvill Secker hardcover without the dust jacket on. The boards and spine are beautiful. I enjoy our daily post so much more now that our bills come via email so that our letter box is normally filled with things like books, greeting cards, or other nice surprises. I highly recommend this method of upgrading your daily deliveries!