Praying Mantis (Victoria, Australia)

The problem was the insects.

They were all around the house. While it was not as if there were a plague of them, there were at least hundreds of the smaller ones, and dozens of the bigger ones – too many to be normal, Glenda was sure of that. Well, she thought she was sure of that. It seemed that more were arriving all the time. They were multiplying at an alarming rate. She could only identify some of the basic types, as insects had never captured her attention much in the past.

Ever since Alan had left on Sunday evening, Glenda had been feeling less and less her usual cheerful self. She’d been disappointed about missing the trip, but it had seemed obvious that she was coming down with something worse than seasonal allergies or a spring cold, and she’d dared not risk infecting prospective clients. She’d said goodbye to Alan and then taken herself to bed with aspirin and a hot toddy, hoping to soothe her throbbing head and inflamed throat. During the night, she’d awoken gasping from a nightmare in which she’d felt herself drowning – her brain’s way of interpreting constricted bronchia, no doubt. The asthma inhaler had done its job, allowing her to sleep through the rest of the night; but Monday morning brought the added discomforts of swollen glands, aching joints, sore muscles, and a fever that waxed and waned.

Initially, she’d seen only the arrival of the small, dark beetles, which seemed to be everywhere in the garden, having descended en masse on Sunday at dusk, as though someone had put out a sign advertising free dung at the Jarrell’s house. She’d been settled on the couch, surrounded by a sprawl of tissues, books, glasses of water, and juice packs, whilst sipping a mug of soup that she couldn’t taste, when she’d glanced out the back window to see them hovering in little groups and settling in clusters wherever they landed. She’d watched them for some time. She’d listened, too, recognising immediately the source of the strange noises that had played at the outer limits of her hearing while she’d slept: noises that had felt both utterly banal, and obscurely threatening. Whirring, buzzing, busy insect sounds. She’d turned away from the window, huddled under her pile of blankets, and switched on the television to look for an old movie. After a while, she’d fallen into a restless sleep, comforting herself with the idea that they would probably leave overnight, as suddenly as they’d come.

On Monday morning, the swarm – did this qualify as a swarm? – had been there still, showing no signs of diminishing. While making her way down the front drive to get the newspaper and mail, she’d stepped accidentally on quite a few skittering creatures, flattening them under her bedroom slippers with a sickening crunch.

On Tuesday morning, she’d done her best to tiptoe carefully around them when she’d taken the same path down the drive, but still ended up with a few stuck to her shoes. She’d spent the remainder of the day trying to convince herself that nothing out of the ordinary was happening. She just wasn’t used to country life yet. Probably beetles swarmed here every year … Maybe.

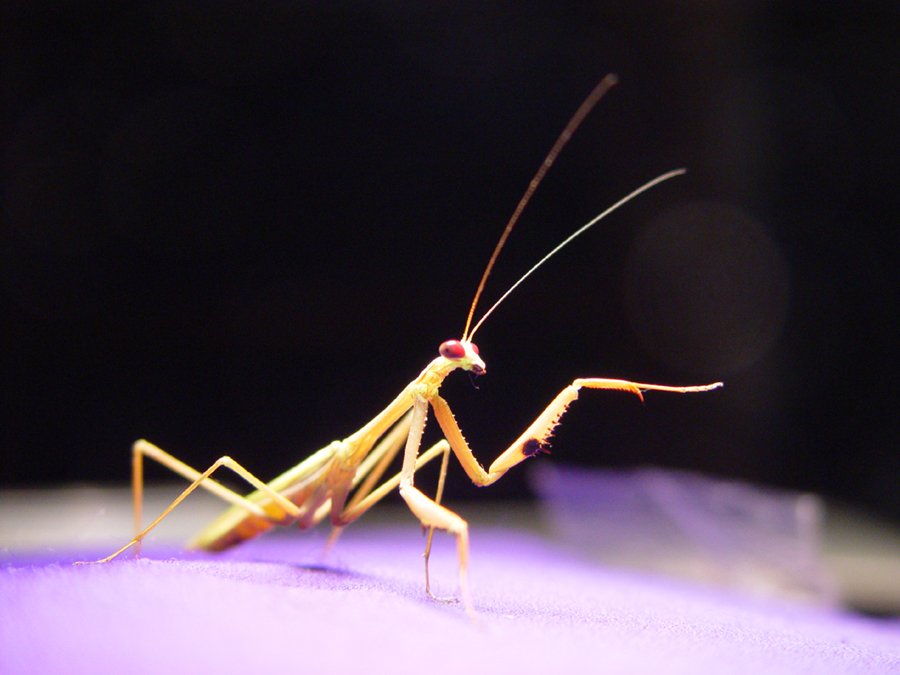

The dragonflies and praying mantises arrived at dusk – fewer in number than the beetles, but still plentiful, and bizarre in their synchronicity. A slight panic set in. Glenda decided to master her rising anxiety by educating herself on local insect behaviour. She was curious by nature and an accomplished researcher by profession, so when mysteries appeared in her life, she felt compelled to solve them. This was far outside her area of expertise.

Sprawled on the couch with her laptop, sipping hot tea laced with honey, lemon, and whiskey, she’d trawled through on-line information about insect invasions common to this part of the countryside. She’d hoped for explanations that would normalise her increasingly abnormal situation. Hours later, blurry-eyed with fever and weary from her efforts, she’d found nothing especially helpful. If they’d lived on a farm, the swarming would have made sense; but what could they want here? As far as she knew, Alan’s and her few hectares of land, abundant with native flora and fauna, did not offer anything extraordinary in the way of nutrition for them. She would have liked to ask some neighbours for their advice, but their nearest neighbours were several kilometres away, and strangers to them. She could not muster enough energy for the journey, or for a casual getting-to-know-you chat over cups of tea.

The one comforting thing she had learned during her on-line research was that some people – especially children – experienced disturbing hallucinations from the flu antiviral she was using. Could that be the problem? She’d been taking some of Alan’s leftover medication from last flu season; perhaps she was having an atypical reaction? Having said that, she could not remember having reacted that way in the past; still, such things were not unheard of.

She tried to laugh at herself for brewing insidious visions of hell in her over-heated brain, compliments of high fever and bad chemistry, but could not find the humour in it somehow. She wondered how – if she were imagining the whole thing – she could prove that to herself. What sort of reality-testing would be fool-proof? She felt more-than-usually revolted by the thought of touching the insects but she supposed that was due to her illness, which had increased her sensitivity to everything. Besides, what if her hands did not clamp together over airy visions? She shuddered. The beetles were the most easily caught, she figured; but how many would she have to feel to be convinced? Besides, would the feeling of fervently-beating wings and scratchy legs against her palms really prove anything? Couldn’t hallucinations be tactile, as well as visual and auditory?

Glenda and Alan had left their respective jobs in the city to move to the outskirts of this quiet country town only four months ago. Everything still felt new, and they were still in the developmental stages of their business partnership. She had initiated the move, wanting a fresh start after the difficulties of last year. She’d longed to immerse herself in nature, and to enjoy the change of seasons that she’d hardly noticed in the city, except for the weather compelling her to add or subtract layers of clothing. She had not envisioned herself isolated during a bout of illness, with legions of creeping things gathering around her with what – in her mounting paranoia – felt like malevolent intent. She reflected on a curious fact of life: that many things which were inoffensive, or even desirable, in small numbers became disgusting and frightening when multiplied exponentially. Perhaps butterflies would have been different, but she’d seen no butterflies. She realised she was probably delirious and therefore irrational, but her vulnerability evoked a quick surge of yearning for the comforts of their tiny flat in the city, and the familiar clutter of the urban landscape.

She decided to stop taking the pills, just in case they were the problem, figuring that her body should manage to fight off a flu on its own. She fell asleep with her laptop still open, a praying mantis with bold red eyes staring out at her from the screen.

When she awoke, it was morning, and she felt right away that things had not improved – not with the illness, and not with the hallucinations, if that’s what they were. She crawled off the couch shaking and covered in sweat, partly from breaking fever, and partly from her daytime anxiety having followed her into sleep, transforming her usually peaceful dream time into a haunted world. After a soothing cup of tea, she felt calmer and remembered only fragments of her nightmare, but its ghost lingered, nevertheless. She did not venture outside for Wednesday’s paper and mail.

She closed the curtains over most of the windows in the lounge room, allowing only slashes of sunlight to break through here and there. All day, as she drifted in and out of sleep, visions of insects crawled through her mind: a barrage of beetles invading the house via air ducts and slivers of space under doors; mounds of dragonflies encrusting the window ledges, staring in at her with a studious and incomprehensible curiosity; orderly praying mantises gathering like pagan priests around a dead lizard they’d managed to overwhelm in a frenzy. Their collective soundtrack was nearly drowned out by the intermittent, shrill staccato of a lone cicada, secreted somewhere in the garden.

Glenda tried to shake off the crazy fears that accompanied such visions. She fought the urge to lock herself in the smallest room of the house and duct tape all the entrances, but then decided that some evasive action would be necessary in order to keep her from completely falling apart after sunset. This is what led to her closing all the vents in the house, and stuffing towels in the gaps beneath doors. No matter what she did, though, she knew she would not be able to block out the sounds. After this hurried bit of work, she made tea in her favourite china pot, but then dozed off again before it finished brewing.

She awoke hours later, as the sun was lowering itself into the hills. The cicada had fallen silent, but she knew with dead certainty that the sound she heard outside the plate glass windows of the lounge room was the hundreds or thousands of beetles, munching grass and whatever else they had discovered in the garden. She stood and walked over to the windows, peering out onto the back patio which she had decorated with two white Adirondack chairs and two dozen potted plants. The chair and the plants were mostly black now, coated with beetles. The munching was constant, and nearly rhythmic. Were they eating her plants? She would not go outside for a closer look.

She tried to dismiss her thoughts as mad.

“You cannot hear beetles eating, Glenda, for heaven’s sake!”

Oh, but she could.

She checked her temperature, which felt nearly normal, but she took a couple of aspirin, anyway, because her head and muscles still hurt.

She checked the seals on all the vents and doors again.

She decided to have a bath.

She noticed with relief that it was near time for Alan to phone. She brought the hands-free phone into the bathroom with her, so she wouldn’t miss him. He’d been calling each evening, but Glenda had avoided mentioning her anxieties about the insects, and had pretended rapidly improving health. It was enough that he called, enough that he loved her. Just hearing his voice each evening helped to ground her, made her feel safer.

She did not want to worry him and distract him from his work – especially since it was their shared work, and she was not there to do her part. It was lucky that she’d taken ill rather than Alan, though. Glenda had superior research and writing skills, but Alan had extraordinary salesmanship. Right now, they needed clients and work contracts, which would require winning people over and gaining their confidence. Glenda was mulling this over, reclining in the bath, and sipping a fruit smoothie when the phone rang.

“Hi, Honey, it’s me.”

“Oh, Alan, I am so happy to hear from you. How are you?”

“Good … very good, in fact. Things are going well here, and it looks like at least two of the groups I’ve met with so far are interested in our work. I’ve got my fingers crossed, Glen, but I feel sure we are going to get at least two, and possibly three, contracts out of this trip.”

“That’s fantastic, darling – really great to hear – and a relief, isn’t it?”

“Yes. I think all our changes are about to start paying off, honey, so we can relax a bit. Lots of work to do, but less stress about our income … More importantly, though, how are you feeling?”

She hesitated.

No, she couldn’t. Even as she caught sight of the dragonflies landing on the skylight over the bath, she knew she could not tell him. He’d been gone only three of the five days that the trip required. If their business were to flourish, it would need a solid customer base. The few contracts they’d had so far had been short term and sporadic, and this move had stretched them financially. They could not afford to miss opportunities.

“I’m much better.” She did not sound convincing, even to herself. “I mean, it’s hard to know. You know how flu is. You feel like your completely dying sometimes, and only half dying the rest of the time … but, after a week or so, you’re suddenly all better, right?”

“Yeah, I guess so. I wish I were there with you, though. Has your fever broken? Have you continued taking the meds I gave you?”

“Yes, the fever has broken for now. And yes, too, about the meds.” She resented herself even more for this half lie. She’d not taken any of the pills in the past twenty-four hours.

“Well, if you are not feeling a whole lot better by tomorrow, would you promise me you will call Dr. Mantis?”

“What did you say?” Glenda sat up straight in the bath, her eyes still watching the insects that walked two metres over her head. There were more of them now, twice as many as when she’d started her bath. She could hear their legs scratching on the plexiglass.

“I said, will you promise me you will call Dr. Matthias tomorrow, if you’re not much better? She can either advise you or recommend someone you can see in the area. I know how much you dislike going to doctors, but I am concerned. No matter what you say, I am not convinced you are getting well. You sound terrible, and you’re all on your own out there … in fact, maybe I should just come home … ”

“Darling, I really am okay. I am having a hot bath and drinking a smoothie, so how bad can I be?” She tried hard to smile, willing him to feel her reassurance through the phone, a thousand kilometres away. “Please, just do your work – our work – and then come home to me as soon as you can. I’m really looking forward to seeing you on Saturday. I miss you.”

“I miss you, too, honey. Well, okay then, I’ll think about it, but I might catch a plane back before my scheduled flight. Right now, I’m heading out to meet Greg and his wife for dinner, so I should go. You remember Greg, right? One of my old school mates?”

“Yes, of course. Say hello to them both for me, and I hope you have a good time catching up. I love you, Alan. Please look after yourself.”

“Of course I will. I love you, too, Glen. And remember, if you are not better …”

“Yes, I know. I will phone Dr. Matthias. Bye for now, sweetheart.”

He blew her a kiss through the phone. He was silly and sweet that way. And for just a moment, Glenda felt soothed enough to forget her fears. She stopped watching the skylight.

…

Glenda slept in the bath and dreamt of their baby. In the dream, she had not miscarried well into her second trimester, as had happened in real life. She had not been rushed to hospital in an ambulance, having nearly bled to death from an internal rupture on the way. She had not awakened to her husband, in tears, saying to her that their baby had not survived, but thank God she had.

There was none of that: in the dream, all was beautiful. Their dream baby was at least six weeks old, healthy and vibrant, and sound asleep in her crib. Glenda was her usual not-sick self, only happier because their little daughter had arrived safely in the world. She was abstractly aware of being both in and out of the dream – present in their old flat, yet also hovering somehow on the periphery, watching the scene unfold.

It was late, and she was alone with the baby. She was waking from having fallen asleep on the couch while watching the news. The news was still running, but the sound on the television would not work, so she could not understand the full context of the images flashing by. They all seemed to be stories about swarms of insects devouring crops, devastating farmers’ lives and the lives of those who depended upon them, throughout vast swathes of countryside. Hungry children stood in queues, some crying, all reaching out empty bowls towards headless adults – the camera was cutting them off at the neck – who doled out rice to them. The children seemed to be crying because there was not enough rice for them all, and the adults were clumsy, repeatedly spilling whole spoonfuls of grain onto the dusty earth.

She tried to remember where Alan was, but could not recall the details of why he wasn’t home at this hour. She went to check on the baby, quietly approaching the crib in the nursery; but even before she reached it, she could feel that something was wrong. In the seconds it took for her vision to adjust in the dark, she began to make out the shape of an enormous insect – as long as the baby herself – resting on the infant’s chest, which laboured under its weight.

She did not scream – there was no sound in this dream – but neither did she hesitate. Grabbing a blanket, she threw it over the monster, before wrapping her arms around it and pulling with all her might. But holding tight and tugging hard only caused the thing to fasten itself onto the baby, as if claiming her for its own. The child began to cry soundlessly. Glenda knew she was struggling for breath and terrified, even without seeing her face.

Glenda tried but failed to shove her body between her little girl and her attacker. She slapped and punched its head, and used her arms and elbows to chop at its legs. Her efforts only provoked it. It reared up, and she could see it fully for the first time: a formidable praying mantis, with its wings spread out, forelegs splayed wide. As it reared, Glenda tried to dive beneath the forelegs to reach her baby, but she was not fast enough.

The thing hissed and struck out, lashing her face. Glenda felt a searing pain down her left cheek. She readied herself for a fight. Her eyes swept the room, seeking a makeshift weapon, but everything – save the crib, the rocker, and the changing table – was soft and round. It was a room filled with tender objects, chosen with love. Then, the baby wailed – the dream becoming horrifically audible, at last – and Glenda heard her own voice responding with a primitive, howling despair.

She woke up moaning and splashing water everywhere, and scrambled out of the bath. She figured herself lucky that she hadn’t drowned, but the bath had grown cold, and the room itself even colder. She was shivering, and her fever was back. And her overwhelming loss. That was back, too, as fresh as the day it had happened.

“Holy hell, Glenda, what is wrong with you?!”

Tears filled her eyes as she cursed herself. It was not the grief that angered her. She understood it took time to heal, and she allowed herself that. It was this damned insect obsession she didn’t understand.

Why couldn’t she just relax? Alan would be home soon, and she would recover from this bout of flu or whatever it was. If, in fact, these insects were gathering around their home in unnatural numbers … Well, they could decide what to do about that together.

She was half convinced she was delirious, and half not. She tried to reason with herself that, if the insects were hallucinations, then they could not hurt her, and that, if they were real, they meant no harm. So why did they feel sinister? Was country life making her crazy?

Glenda heard a tapping sound, like someone using a fingertip or a key on the aluminium edges of the flyscreen door.

She froze, but chided herself for it. “It’s just the door. That’s totally normal.”

Another tap.

She rushed into the bedroom, pulled on a thick robe, and hurried to see who was there. Even as sick as she was right now, it would be good to see another human face and exchange a few words of greeting with someone. As she stuffed her feet into her bedroom slippers, she noticed that a few smashed beetles came unstuck from the soles, and fell to the ground. She kicked them aside. That felt real enough all right.

Another tap and she was at the door.

Peering through the peephole told her nothing. No one stood on the porch waiting to sell her a mobile phone service, a new electricity plan, or personal salvation. Yet, she was sure she had heard a tap. Three taps, in fact.

Glenda went into her kitchen, pulled out a carving knife and stuck in her robe pocket, then returned to the door.

She opened it and looked around, but saw no one.

She stepped onto the porch and stared upwards, taking in what remained of the day as it lingered in a dusty blue sky that reminded her of faded flannel. Shaggy grey clouds, static as glued-on paper cut-outs, overlay the blue. The icy smile of a crescent moon dangled Venus brightly from its left tip. All reassuringly normal and beautiful. She knew that the scents of blooming wattle, and the oils of lemon and peppermint Eucalypts, were surely wafting to her on the lingering warm air, and this would have lightened her spirits considerably had she been able to smell them.

She could see a Ringtail Possum staring out at her from the Feijoa tree in the sprawling front garden. Several fruit bats swooped overhead, coming to land on the Angophora, to which they’d taken a liking lately. A band of Sulphur-Crested Cockatoos was carrying on – raucous as footy players at a pub, as usual – in another nearby gum tree. She watched and listened as the cockies screeched to one other and half-destroyed her tree, ripping branches and leaves to shreds and tossing gum nuts to the ground. She knew they did this to sharpen their beaks, but she suspected they did it just for fun too. She appreciated their cacophony, because it almost drowned out the insect sounds emitted by the gatherings of them which blackened several of the shrubs in the front garden, and settled like a dark carpet over the lawn. Almost.

Glenda felt herself swooning. She steadied herself against the low wall that enclosed the porch, grateful that the porch on this side of the house was two metres above ground level, so the insects were not very near to her. Pobblebonks and southern brown tree frogs called from their respective ponds, mingling with the happy chortle of a few magpies, and the disgruntled cawing of a raven. These sounds comforted her, too. As much as she appreciated them in their own right, what she liked most just now about frogs and birds was their reliable habit of devouring insects. The invading army would not last long with these allies around. A murder of magpies? A conspiracy of ravens? Yes, those would do nicely, thanks very much. But, she was kidding herself, really. Unless some of the littler birds showed up – like finches and robins – the insects were probably safe. The frogs wouldn’t bother to leave their ponds to save her, either. They’d settle for the edibles closest to them, surely.

She’d hoisted herself away from the wall and was about to re-enter the house when she saw it: a bright green cicada, standing on the mat just inside the front door. For a moment, she stood there like she’d grown roots, staring at it. She had known that at least one was around the place. She had not believed it to be one of the hallucinations that she was (or was not) having, since everyone knew that the Greengrocers were common this time of year. Besides, she’d assumed that even hallucinations had a decibel limit beyond which they could not go. This type of cicada was one of the loudest insects in the world.

Yes, she was sure that this particular visitor was real. She found that its realness did not make her feel any better. Under normal circumstances, Glenda did not fear Greengrocers; in fact, she’d been known to hold one now and then, to admire its lovely colour and form. But she’d never had one tapping on her door to be let in before, and given the current context, it felt ominous.

She watched as it move farther into the foyer, undisturbed by her presence. She reasoned to herself that it was escaping the birds that, no doubt, had been pursuing it. The taps had been nothing more than its flinging itself against the aluminium of the flyscreen door, seeking refuge. She had rescued it. Now all she had to do was pick it up and relocate it to a safer place, away from the loitering birds, but outside her house. After all, it was only a small and harmless creature in need of help.

She told herself all this. Yet still, she could not go in after it. The nightmare image of the monster praying mantis glimmered at the edges of her mind. She imagined herself plucking the cicada from the floor, and watching it grow gigantic in her cupped hands, like a maleficent genie escaping its bottle …

Suddenly, outside felt safer than inside, at least until nightfall. She went back out to the front porch, where she sank dizzily onto a stone bench and leaned her back against the warm red brick wall. Her head throbbed, her body trembled, and her teeth chattered from the deepening chill that consumed her, despite the warm weather. She closed her eyes, just for a moment, and drifted into a half-sleep. Some time later, when she opened them, the faded blue flannel sky had deepened to a soft black, and the shaggy clouds had cleared the way for starlight.

She checked for the cicada. It was still there on the mat. How long had she been sleeping? She was covered in sweat but was no longer cold, so she realised her fever had broken again.

The cat approached in stealth and silence, bounding up the porch steps from the garden like some kind of phantom in a silent movie. Though a stranger to Glenda, it glided past her with the self-possession inherent to its kind, without acknowledging her. It was hyper-focused on the prey it had been tracking, apparently for some time.

Its pounce was singularly brilliant.

Glenda watched the cat leap in a perfect arc, landing squarely on its target. An unholy noise erupted from the foyer – the cicada having only this harsh music for a weapon. Glenda covered her ears, which hardly seemed to make a difference to the intensity, but the cat never faltered.

The insect was quickly disabled, and finally silenced. The cat tossed it into the air and batted it around the entrance hall for a while, before picking it up in its teeth, and leaping onto the stone bench. It dropped the corpse between them, as an offering, before settling down next to Glenda.

Normally, she would have been a disinterested observer of such an unremarkable scene. There were so many tiny murders happening all the time in the insect world. They were routinely crushed underfoot, splattered against windshields, and sprayed with poisons to rid them from kitchens. Normally, she would not have considered mortal combat between a house pet and an insect to be worthy of devout attention, as though they were chivalric knights defending the honour of a virgin, or heroes deciding the fate of the ancient world. Normally, she was not consumed by fear of small winged creatures with screechy voices. This unexpected act of savage grace felt like deliverance.

Glenda stroked the cat’s head, and then took it inside and opened a can of tuna for it. It was not unusual to find strays in the country – she knew that – but this one did not seem like a stray. She had a good look at him. He was a healthy ginger-cream tom, with a bountiful coat that felt clean and smelled fresh when she pressed her face to it. She found no collar or tags. Why would he wander off from a home where he was clearly well cared for? But then, cats were like that, especially toms.

She swallowed two aspirins, drank a cup of tea, ate another bowl of soup she could not taste, and then curled up on the couch with the cat to watch television. She’d worry about his family tomorrow; for tonight, she was glad he was hers. She fell asleep in a world that felt safe again.

…

Alan arrived home after midnight with a bottle of bubbly tucked under his arm. On his way to meet his friends for dinner, he’d received back-to-back phone calls confirming the two contracts he’d been hoping to win. He would have to follow-up with the last group via teleconference, but even if that fell through, there would be plenty of work to keep them going for a year or more.

He found Glenda half-buried by blankets, and surrounded by the paraphernalia of a sick room: tissues, juice packs, water bottles, a pot of cold tea, and some left over soup and tuna. Tuna? Well, she must feel better if she could eat that.

At first, he was concerned to see a carving knife on the coffee table, but then realised she must have been spooked by a noise or something. He kissed her forehead, which felt cool, and noticed she seemed to be sleeping peacefully. Still, he was glad he’d come home early, to see for himself that she was all right.

Amongst the jumble of blankets, Alan was perplexed to see Glenda clutching a sweater his grandmother had knitted him when he was a teenager. He’d kept it for sentimental reasons, but rarely took it out of his closet, because it was unwearable, as far as he was concerned. As a redhead with hair the texture of spun-sugar, the last thing he’d ever needed in his wardrobe was a pullover of ginger-cream angora.

Ginger Cat (Image source)

Main photo by Robin Whittle.

Text by td Whittle.